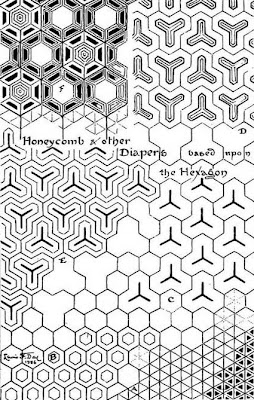

Illustration: Lewis Foreman Day. The Lattice and the Diamond, from The Anatomy of Pattern, 1887.

In 1887, the English designer and critic Lewis Forman Day published the book The Anatomy of Pattern. It was one of a series of important and influential books that he wrote during this period, which saw the nineteenth century slowly draw to a close.

Books that classified the differing styles and accomplishments of both architecture and decoration had been published for centuries in Europe. However, ones dealing specifically with decoration and ornament were particularly popular in the eighteenth century and continued to be so in the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. The myriad titles produced over this long period of the decorative arts tended to deal with the specifics of technical and practical knowledge for the professional decorator. Many of the books gave detailed drawings of decoration that could be used in a variety of situations from the wealthy to the less so.

Illustration: Lewis Foreman Day. The Triangle, from The Anatomy of Pattern, 1887.

However, it was not until the nineteenth century that there began a form of rationalisation of decoration and ornament. Books began to appear that were aimed at the understanding of decoration and pattern. It was thought by many that rather than aimlessly copying a particular style, it was perhaps better to understand the anatomy of that particular decorative style. In many respects, this both changed the knowledge base of individuals involved in the decorative arts, but also helped to push forward a much more fundamental respect for, and understanding of, the vital and fundamental elements of the vocabulary that went to make up the history of decoration.

Day's approach to understanding decoration is particularly interesting, as he seems to be well aware that information concerning the anatomy of pattern itself could often be sketchy and ill taught. Therefore, in his short introduction to The Anatomy of Pattern he quickly draws attention to the fact that:

Illustration: Lewis Foreman Day. The Hexagon, from The Anatomy of Pattern, 1887.

'There was a time in my own struggling for artistic existence, when I should have been so grateful for any practical teaching in ornament, that I fancy there must be students who will find it helpful to have set plainly before them what I have had to puzzle out for myself.'

To be fair these small books could only ever have been meant as a learning tool for younger students who were starting with little or no knowledge of the vocabulary of decoration, ornament and pattern. However, these booklets would have been supported by a whole range of books that began to appear in the nineteenth century, even before Owen Jones The Grammar of Ornament in 1856. They were particularly popular in Britain, France and Germany and although many were initially based on the different aspects of classicism, the genre soon broke free and books began to appear with a number of differing and often increasingly interconnected themes.

Illustration: Lewis Foreman Day. The Octagon, from The Anatomy of Pattern, 1887.

Two of the most popular from the mid-nineteenth century onwards would have been that of medieval and Islamic decoration and it is interesting to note that Day himself places a certain emphasis on the basics of both pattern systems. What is even more interesting is how fundamentally similar are the founding structures of decoration. Day clearly implies through drawing and text that all decorative styles can be drawn with a few basic design and decoration rules. With a simple skeletal form many styles of pattern can be hung. This revelation opens up a world of infinite variety and possibility for the young student, which is its implication.

Illustration: Lewis Foreman Day. Diapers of Circles, from The Anatomy of Pattern, 1887.

Day's series of small books which also included The Application of Ornament and The Planning of Ornament, although by no means weighty tomes describing every detail and minutiae of decoration and ornament, were still inevitably able to inspire the student to understand the creative possibilities that could be fostered by a simple analysis of the rules that governed the vocabulary of pattern work. That it may well have taken successive generations who produce these rules and guides, goes without saying. Ultimately praise of their often anonymous achievements, which helped to produce the themes for Day's books, would inevitably have been silently dedicated by the author.

A glance at the Further reading links section below will give some indication as to the breadth of subject Day covered in his numerous publications. More examples from a number of Day's books will inevitably follow as articles on The Textile Blog in the coming weeks and months.

Further reading links:

Art nouveau embroidery =: Art in needlework

Nature and ornament;: Nature, the raw material of design

Penmanship of the Xvi, XVII and Xviiith Centuries: A Series of Typical Examples from English and Foreign Writing Books

Windows

Pattern design: A book for students treating in a practical way of the anatomy, planning & evolution of repeated ornament

Alphabets old and new, for the use of craftsmen: with an introductory essay on Art in the alphabet

Ornamental design, embracing The Anatomy of pattern: The planning of ornament; The application of ornament

Every-Day Art; Short Essays on the Arts Not Fine

Stained Glass

The Anatomy of Pattern

Nature In Ornament; An Enquiry Into The Natural Element In Ornamental Design & A Survey Of The Ornamental Treatment Of Natural Forms

Ornament & its application; a book for students, treating in a practical way of the relation of design to material, tools and methods of work

The application of ornament

Enamelling, a comparative account of the development and practice of the art

Alphabets old & new: Containing over one hundred and fifty complete alphabets, thirty series of numerals, and numerous facsimiles of ancient dates, etc., ... alphabet" (Text books of ornamental design)

Every-Day Art