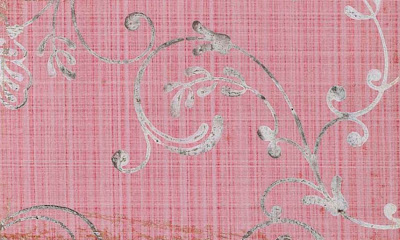

Illustration: French wallpaper design for a drawing room, 1849.

French wallpaper design during the mid nineteenth century, it is fair to say, was not on the scale of that being produced in Britain. However, although the scale of production in Britain was one that was difficult to compete with, this did not necessarily mean that the standard of design was also competitive. Britain could be proud of the fact that its wallpaper retail trade was by no means elitist, and in fact supplied a relatively cheap product to a large proportion of the general public. However, there were particular problems when it came to the standard of pattern work achieved on many examples sold in Britain and this became more acute when compared to those being produced at the same time in France.

The three examples illustrating this article are French derived wallpapers that were imported and then sold across Britain in about 1849. It was a relatively common practice in Britain to sell both home produced and foreign sourced wallpapers. The first two examples were imported by W B Simpson and the third by Jackson & Graham, both companies trading from London.

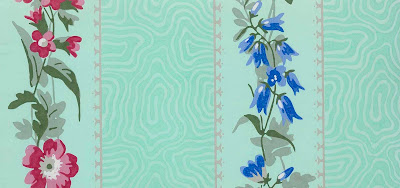

Illustration: French wallpaper design for a bedroom, 1849.

Most imported wallpapers would have been French. To a certain extent this would have been for the long standing reason that in Britain, France had a long and illustrious reputation for high standards in interior decorative accessories and therefore anything French would have sold well as far as the British retail trade was concerned. However, the reputation was not an idle one as French decorative work was considered to be consistently of a higher standard than the British equivalent. This became more acute when the industrial revolution took over the process of interior accessory production across Britain, where most of the hand produced work disappeared leaving only a very small niche market for those that could afford any form of hand production. Although industrial processes were also widespread in France, detailed hand production still survived as did the French reputation for quality over quantity.

Interestingly, the first two French examples in this article were produced using both machine and hand block printing. All of the first example which was produced ideally for a drawing room, was produced using a cylinder printing process, except for the gilding which was applied by hand block printing. Ironically, the hand-produced gilding actually detracts from the pattern work and seems crudely applied, which is a shame as the pattern itself is very finely tuned and seems almost effortless in its composition.

Illustration: French wallpaper design for a bedroom, 1849.

The second example, produced ideally for a bedroom, had a machine produced background, with a block printed foliage inspired pattern. The industrial process has been limited to a background filler and took no part in the more obvious pattern process. This combination of machine and hand production was a relatively successful process that perhaps should have occurred to British manufacturers as a viable option, particularly when considering the low standards being regularly achieved by British companies using full automation.

In the third example a certain amount of hand block printing was used, though it is unclear if it was entirely hand produced and could well have been a compromise production of both hand and industrial process, as in the first two examples. Whatever the case, it is a fine example of quality production from France, even though the same industrial process as was used extensively in Britain was still part of its manufacture.

This does not necessarily imply that hand production should always be seen as superior to that produced by industry. However, it certainly does imply that the human creative process should be uppermost when considering mass production. When the human element is extracted from the industrial process, leaving little or no room for genuine intuitive flair and creativity, the result is flawed and by its very nature, monotonous. This genuine Achilles heal within the industrial process would ultimately be picked up and intensely highlighted and criticised by the Arts & Crafts movement in particular. Ultimately, it should be remembered that whatever factory or industrial process is used to produce mass manufactured goods, all of those goods will eventually end up in the hands of a human individual. In that respect, understanding the point and usefulness of a product should always have the human element firmly in the centre of its being.

Further reading links:

French Scenic Wallpaper 1795-1865

Wallpaper: The Ultimate Guide

Wallpaper in Decoration

Wallpapers of France, 1800-1850

Off the Wall: Wonderful Wall Coverings of the Twentieth Century

Wallpaper, its history, design and use : with frontispiece in colour and numerous illustrations from

WILLIAM MORRIS WALLPAPERS AND CHINTZES.

Wallpaper in America: From the Seventeenth Century to World War I

Fabrics and Wallpapers for Historic Buildings

French Interiors of the Eighteenth Century

Parisian Interiors

Parisian Interiors: Bold, Elegant, Refined

Victorian Interior Decoration: American Interiors : 1830-1900

Victorian and Edwardian Furniture and Interiors: From the Gothic Revival to Art Nouveau

Hints on Household Taste: The Classic Handbook of Victorian Interior Decoration

Principles of Victorian Decorative Design